Limiting & Supplying Roadway Speeds

Intro

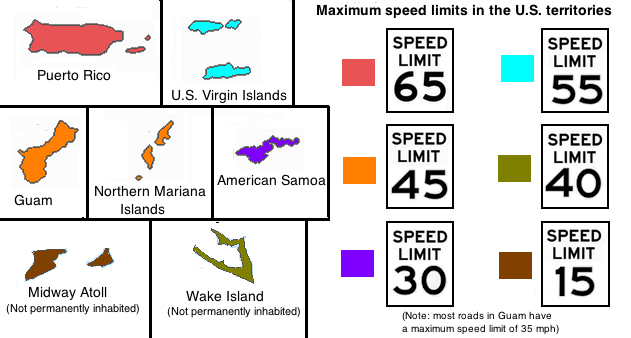

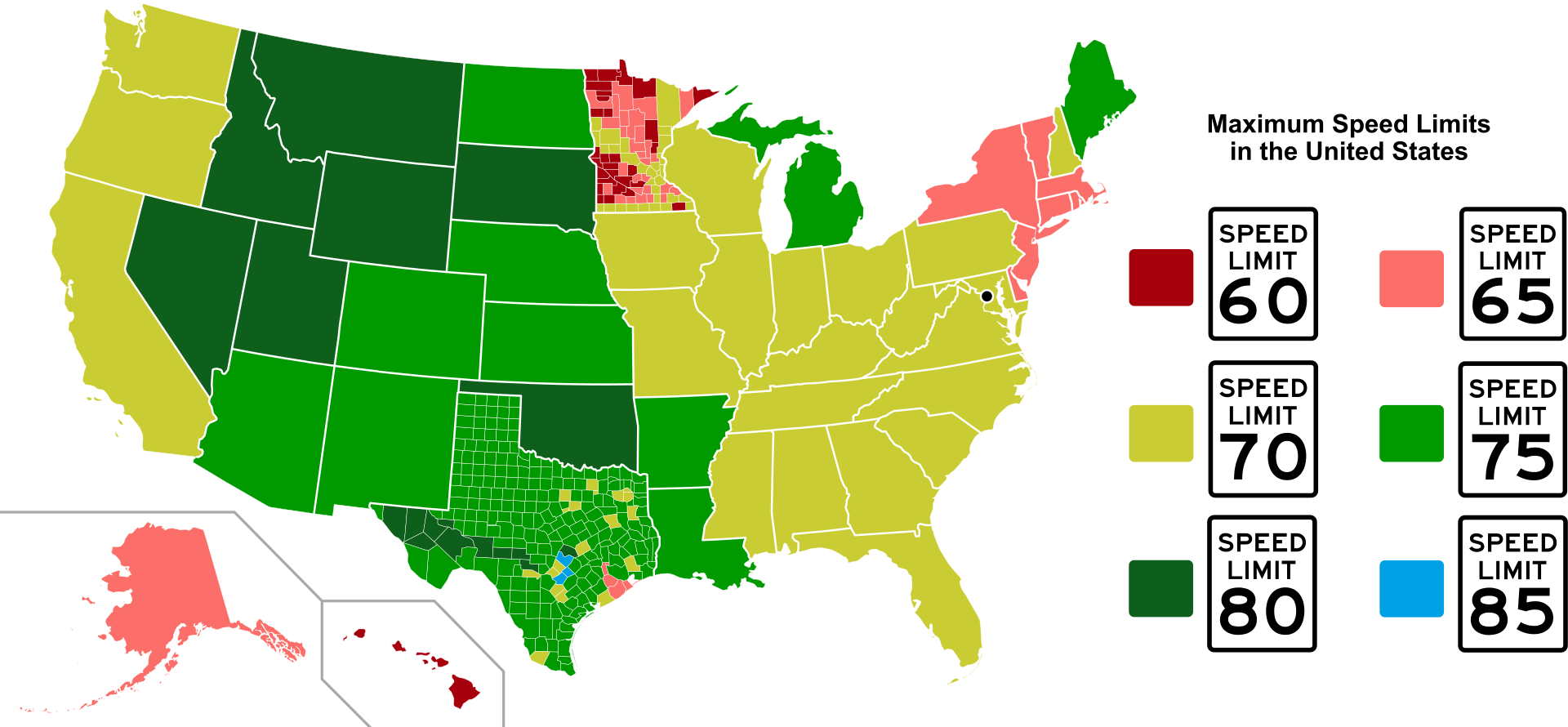

The US is a country containing a wide variety of landscapes. This calls for roadways with, not only varied speeds; but also varied policies. Tangling a web of half arbitrary guidelines ranging from a speed limit of 85mph (137km/h) on a single stretch of tollway outside of Austin, TX; decreasing to the speed limits imposed on the US territories. Bottoming out in American Samoa, where the maximum speed on the island is 30mph (48km/h). Though, on most major roads in Guam; 35 is the normal as well. If you want to count the primarily uninhabited territories of the United States as well; Midway Atoll would take the slowest speeds with 15mph (24km/h). I’m sure they’re more worried about knots in those parts anyway.

The combination of the considerable range in speed between the regions and the policies enacted by 50+ different state and territorial governments allow for plenty of tiny differences spanning the safe and the unsafe. The overuse and placement of signs create visual clutter and confusion for drivers. Furthermore, it can and has created an unsafe environment for anyone outside an automobile. Decisions as varied as these are sent right down to the city with just as detailed quirks shaped by policy and history. At this point you’re probably thinking, “speed limit signs…big whoop”, but I implore you read on for the surprisingly interesting history and psychology of speed limits in the United States.

Cincinatti

Speed limits in the United States are known to date back to 1701 in Boston. Naturally, the first speed limit signs were posted at city and town limits. In the early 20s, right when US passenger and freight rail was at its most accessible with steady profits post World War I; cars were becoming an evermore common sight in cities. Along with automobiles came the safety and organizational changes that altered the urban fabric of US cities. Cincinatti was no exception and as soon as 1917, before the war even ended; Cincinnati tried to negotiate a truce between foot traffic and motor traffic with the implementation of new laws. Motorists could go no faster than 8mph (13km/h) in the city’s business district and 15mph (24km/h) in residential districts. At this point, it is important to remember Cincy’s streets (as with every other US city) were bustling overwhelmingly with foot traffic actually using with entire width of the street. Furthermore, with the passage of the new laws pedestrians were restricted to sidewalks and crosswalks. Created the basis for what would later be known as ‘jaywalking’

According to Cincinatti Magazine, “Among the first arrested [for jaywalking] was Miss Ella Bright of Clifton; a teacher at Woodward High School.” On June 7, 1917; wrote The Cincinatti Enquirer, “She declared she has been upbraided unduly by an officer because she crossed the street in a manner which was a violation of the traffic laws after alighting from a streetcar.” Arrests of pedestrians just trying to cross the street continued to increase as 1917 slowly ticked by. However, what about the motorists? Were they following city speeds? Well, as pedestrian fatalities mounted the motorists generally ignored the speed limits. All the while, they cracked down on horse drawn carriages and wagons. Absolutely and nonsensically ignoring the real cause of the increased fatalities. So was the corrupted US political landscape of the ‘20s. With an act of protest in mind, In June 1922, an ‘Initiative Committee’ announced it would began to gather signatures to place on the next ballot an ordinance requiring all automobiles operating within Cincinatti city limits to be equipped with what they called at the time “a mechanical speed regulating device.” These early ’speed governors’ would physically prohibit the vehicle from traveling at speeds greater than 25mph (40km/h).

Revealed later, among the donors to ’The Initiative Committee” was but one person. A Wyoming resident; Walter F. Pentlarge was the president of the United States Bung Manufacturing Company who contributed the entire $1,392.66 budget to promote the speed regulator ordinance. Of course this initiative would go on to fail and 2,200 individuals (including some large corporations) donated $7,365.50 to the opposition Citizens’ Campaign Committee. The opponents of the city ordinance cited that speed governors were useless going downhill, when the driver could shift into neutral and coast going downhill.

What Can We Learn From This?

Dying at the ballet box. Only 14,012 voters supported the speed governor proposal, while 92,427 opposed. Even if it would’ve miraculously passed I believe it probably wouldn’t be imposed in the most just of ways in a bootlegging America segregated in vast ways. Could it be done today? Probably not. Should it be done? Probably not. As Norway and The Netherlands have proven time and time again. The physical throughway design is the almighty factor in the speed of a driver. Aspects of a street including, but not limited to; tree canopies, medium rise buildings, one way roads, and close in walking and biking infrastructure are key features to have to naturally slow down speeders. Aspects, I should way, a typically does not have. With this Cincinnati study in mind I must say that vehicle size is something we should consider more in the US when we think of the safety of our streets. Something I’ve covered before.

The problem of car dependency and the beginning of activism towards better urbanism in the US started farther back than many like to think. According to Bloomberg’s CityLab, “All over America in the 1950s and 1960s, residents particularly women, organizaerddemonstrations against car traffic.” Even by the 1970s one of five US households had no car. According to research published by the Federal Highway Administration early in that decade, “Among the 10.7 million households in which the family income was less than $3,000 a year, 63% had no car.” The study goes on to say, "Women drove much less than men: About 56 percent of all licensed drivers were men, and according to drivers’ own estimates 73 percent of all miles driven were driven by men. People of color were much less likely to drive than whites. Whites made 52 percent of their trips as car drivers, nonwhites 37 percent. Among school children in 1970, 42 percent walked or bicycled, compared to 38 percent who rode a school bus. Only 16 percent were driven to school.”It seems the more who drive in a given place; the more disconnected from that given place one is.

TX-130, Mustang Range, TX

Montana & The Speed Limit Psychology

Now finally, what happens when the opposite happens. Well, late 1990s Montana can answer that one. Now, how ‘bout a little context. During World War II, the U.S. Office of Defense Transportation established a national 35 mph "Victory Speed Limit" (also known as "War Speed") to conserve gasoline and rubber for the American war effort, from May 1942 to August 1945, when the war ended. For 13 years between January 1974 – April 1987, federal law withheld Federal highway trust funds to states that had speed limits above 55 mph (89 km/h). From April 1987 to December 8, 1995, an amended federal law allowed speed limits up to 65 mph (105 km/h) on rural Interstate and rural roads built to Interstate highway standards.

The law was widely disregarded by motorists, even after the national maximum was increased to 65 mph (105 km/h) on certain roads in 1987 and 1988. In 1995, the law was repealed by the National Highway System Designation Act of 1995, returning the choice of speed limit to each state. Upon that repeal, there was effectively no speed limit on Montana's highways for daytime driving (the nighttime limit was set at 65 miles per hour (105 km/h) from 1995 until 1999. One traveler driving through the region during this time was Larry Kenney. A fellow traveler and one half of the travel blog, “Bill & Larry’s Adventures.” When asked what driving through Montana during this time was like; Kenney said, “Actually, we found Montanans to drive slower than folks in many other states and their speed limits in town were quite slow. Their lack of a specified speed limit appeared to be more out of a respect for individual judgement and for one another than it did out of daredevil attitude.” He went to say, “West must admit it was pleasant to drive what was safe and not have to constantly eye the speedometer during our visit to Montana in July 1997.”

Montana State Line, 1997

When the Montana State Supreme Court threw out the law requiring a "reasonable and prudent" speed as "unconstitutionally vague.” The state legislature enacted a 75 miles per hour (121 km/h) daytime limit in May 1999. Overall, the new speed limit law in Montana was found to be satisfactory to residents of the state. With Larry’s words and Dutch roadway design in mind; I can’t help but think. Would we need speed limits? If road design was the only hint at what speed drivers were supposed to go comfortably, would it work? Honestly, I think it would better than speed governors, but then again just ride the train.

FIN

Sources //